Post by therealriga on Jun 4, 2020 17:18:36 GMT

In a hypothetical contest to find the most interesting and exciting constituency, Fermanagh & South Tyrone (FST) would be one of the front runners. Its history has been marked by close and dramatic contests, vote splitting between rival factions and controversy. At least 3 elections in the constituency have been decided in the courts. One election in the constituency gained international attention, led to a change in British electoral law and had far reaching effects on regional and national politics. Another MP made a significant contribution to bringing down the government.

For lovers of electoral trivia, the constituency is a godsend. It features prominently in many lists of election records. The highest ever turnout in a Westminster election (93.4% in 1951) , the fifth smallest majority since 1945 (4 votes in 2010) , one of the last constituencies in which a loser became the MP after the winner was disqualified (1955), the most recent constituency in which the winning party had not contested the previous election (2015) and the highest vote share ever achieved by a party with no MPs (UUP, 2019.) Three of its MPs feature on the list of the MPs with the shortest service. Three of the elections this century have been won by less than 60 votes. Elections in FST are never dull.

The constituency was created in 1950 when the two-member Fermanagh & Tyrone constituency was split as part of the final move to single-member seats. As the name suggests, it consists of County Fermanagh and the southern part of County Tyrone. Some areas south of Omagh were removed for the 1983 election, after which it consisted of the whole of Fermanagh and Dungannon (later Dungannon & South Tyrone) councils. Boundary changes for the 1997 election removed 6 wards around the town of Coalisland, north of Dungannon. This area was strongly Republican and its removal boosted the Unionist vote. FST was unchanged in 2010, though the Boundary Commission has twice suggested linking Fermanagh with Omagh instead of Dungannon in its provisional proposals. It is a sprawling and mostly rural constituency stretching for nearly 70 miles from Lough Neagh to Belleek. Since the resettlement of the islanders of St Kilda in 1930, Belleek has been the westernmost inhabited place in the UK.

While the constituency does include areas of prosperity (parts of Enniskillen, Dungannon and the area around Moy) income levels are below the regional average. The percentage of the population living in households of social grade AB was only 12.5% at the 2011 census, the third lowest in NI. 57.7% of the population had a Catholic community background, the seventh highest in NI. This represented a 2% increase on the 2001 census and, despite the close results, the recent trend has been towards Nationalism. The Protestant population forms a majority in the area between Dungannon and the Fermanagh border, the eastern part of Dungannon and north and central Fermanagh. The first of these areas includes Clogher, the last place in NI to lose its city status, which occurred with the 1801 Act of Union. Most of southern and western Fermanagh is 75-80% Catholic, with Enniskillen reaching 65%. In the 2016 Brexit referendum, the constituency seems to have split on sectarian lines, with 58.6% voting remain.

Both the DUP and SDLP were late organising in parts of Fermanagh. In the former case, this ensured UUP hegemony. In the latter case, this left the field clear for independents and smaller Republican groupings such as Unity, the Irish Independence Party and, from the 1980s, Sinn Féin.

The first contest in 1950 was won narrowly by Cahir Healey, who had represented the predecessor constituency until 1935. Aged 72, he was one of the oldest returnee MPs. He held the seat in 1951. The 1955 election saw a narrower victory of 261 votes for the Sinn Féin (SF) candidate Philip Clarke. However, as Clarke was in prison, he was unseated by an election petition and his sole opponent, the UUP’s Robert Grosvenor, was declared elected in his place.

At the 1959 election, the Nationalist Party withdrew their support for SF, instead urging their supporters to boycott the election. This led to a swing of nearly 32% from SF to the UUP, largely down to differential turnout. As a result, Grosvenor won with 81%. At just 61%, the turnout was way below usual. In all other elections from 1950 until the mid-1980s, FST consistently produced one of the highest turnouts in the UK, never falling below 86%.

Nationalist/Republican splits in 1964 and 1966 allowed the UUP to win. However, for the 1970 election, a pact was agreed under the appropriately titled “Unity” label, with its candidate, Frank McManus elected. However, in February 1974, both Unionist and Nationalist sides were split, but the more even split on the Nationalist side – with the SDLP standing for the first time - allowed UUP leader Harry West to become the new MP. His tenure was even shorter than McManus’. Nationalists agreed a common candidate, local pub owner Frank Maguire, who won as an “Independent Republican.” This gave West the unwanted distinction of being the only MP elected in February 1974 who lost his seat later that year and never returned to the Commons.

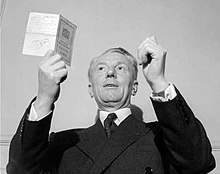

Maguire’s attendance at Westminster was low, but he did play a significant role in that parliament. Usually voting with Labour, he refused to back them in the key vote of confidence in 1979, flying to London to “abstain in person” as he put it, resulting in an early General Election. Maguire’s actions led to disputes within the local SDLP branch over whether to stand. Though they voted in favour of withdrawing, this caused controversy, and one member, Austin Currie, who had previously represented East Tyrone in the NI Parliament, ran as Independent SDLP. However, the Unionist side was also split, with Vanguard splinter group the United Ulster Unionist Party opposing the UUP. This allowed Maguire to hold with a majority of nearly 5,000.

Maguire’s untimely death in 1981 at the age of 51 came at a turbulent time in NI politics. The Hunger Strikes in the Maze Prison had sharply polarised the region. With Unionists agreeing a common candidate, former MP Harry West, Nationalists sought to do the same. Maguire’s brother Noel announced he would stand but stood down after implied threats leaving the way clear for Bobby Sands, the leader of the IRA prisoners, to face West in a straight fight. In a by-election which attracted international attention, Sands beat West by 1,447 votes on an 87% turnout in which over 3,000 ballot papers were spoilt.

Sands died on hunger strike 26 days later. The government rushed through legislation (The Representation of the People Act 1981) to prevent another prisoner standing in the second 1981 by-election. Though some smaller parties and fringe candidates stood, Sands’ election agent, Owen Carron, standing as “Anti-H Block Proxy Political Prisoner” was able to increase the majority over the new UUP candidate, Ken Maginnis.

Sands’ and Carron’s elections had wider significance, proving to Sinn Féin that an electoral route was viable. At SF’s 1981 conference, senior strategist Danny Morrison confirmed a change stating: “Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?” This was dubbed the ”Armalite and Ballot Box” strategy and saw SF contest elections from 1982 onwards. Arguably, FST played a key part on the first step on the road to the IRA ceasefire the following decade.

The SDLP, despite internal division, had not stood in either by-election, but they stood in the 1983 general election. This split in the Nationalist vote allowed the sole Unionist, Ken Maginnis of the UUP to win comfortably, by 7,676. Continued Nationalist divisions allowed him to hold the seat with ease until his 2001 retirement.

One of the more significant events in The Troubles occurred in the constituency. In November 1987, an IRA bomb detonated at the cenotaph in Enniskillen, killing 11 civilians. The murder of so many people, many of them elderly, commemorating war dead appalled many Nationalists and led to a significant backlash against Sinn Féin. In the 1989 local elections, the party lost over a quarter of its council seats, with losses heavier in the west of NI. Fermanagh proved the worst, with the party losing 4 of its 8 seats (another would be lost in 1993.) The party’s support would not return to its 1985 until 2001, well after the IRA ceasefire. The bombing is seen by many as a key turning point in the Troubles and one of the catalysts for the peace process of the 1990s, which led to the Good Friday Agreement. These events led Sinn Féin to realise that the "bullet and ballot" strategy was unviable.

The Agreement led to significant tensions between the two main Unionist parties, so when the UUP selected James Cooper, a staunch supporter of the Agreement, to succeed Maginnis, the DUP refused to endorse him. Instead they backed independent William Dixon, who had been badly injured in the Enniskillen bomb. As was usual in NI elections before 2010, counting did not begin until the Friday morning. FST was the final UK constituency to declare at after 10pm, a full 24 hours after polls had closed. The result was a bitter one for the UUP as Sinn Féin’s Michelle Gildernew beat Cooper by 53 votes. In reality, the margin was even closer. The UUP cried foul, launching a legal challenge and pointing out that a polling station in the mostly Catholic village of Garrison had remained open after 10pm, allegedly after the presiding officer had been threatened by Republicans. An election court found that this had indeed occurred, but that the number of ballot papers issued had been no more than 20, insufficient to affect the result, which was upheld.

For the only time to date, both the UUP and DUP stood candidates in 2005. Although the DUP overtook their rival for the first time, this allowed Gildernew to hold by 4,582 votes, a relative landslide in FST terms.

With relations between the DUP and UUP improving in the late 2000s, a common independent candidate was agreed for 2010: former Fermanagh council chief executive Rodney Connor. With the SDLP refusing to stand down, it was expected that this would return the seat to Unionist hands. However, Sinn Féin portrayed Connor’s selection as a “sectarian pact.” This allowed them to significantly squeeze the SDLP vote. The first count put Connor 10 votes ahead. SF requested a recount, which gave Gildernew an 8-vote lead. A second recount cut this to a 2-vote lead. A third and final recount gave her a 4-vote victory. Subsequent events were a rerun of 2001. Unionists mounted a legal challenge, alleging ballot paper irregularities. However, an election court upheld the result, finding that only 3 ballot papers could not be accounted for, insufficient to affect the result.

Having held on in 2010 and with a general trend towards Nationalism, it was expected that Gildernew could beat the sole Unionist in 2015 as well. In a result that was somewhat of a surprise, she lost by 530 votes to former UUP leader Tom Elliott. Like many of his predecessors, Elliott’s tenure was short. Two years later, Gildernew reversed the result, beating him by 875 votes.

2019 saw a slight SDLP recovery and both the UUP and SF decline. This resulted in Gildernew’s majority falling to just 57 votes, the smallest majority of the election. Despite the trend towards Nationalism, Unionism’s greater success in agreeing pacts means the drama here will likely continue.

For lovers of electoral trivia, the constituency is a godsend. It features prominently in many lists of election records. The highest ever turnout in a Westminster election (93.4% in 1951) , the fifth smallest majority since 1945 (4 votes in 2010) , one of the last constituencies in which a loser became the MP after the winner was disqualified (1955), the most recent constituency in which the winning party had not contested the previous election (2015) and the highest vote share ever achieved by a party with no MPs (UUP, 2019.) Three of its MPs feature on the list of the MPs with the shortest service. Three of the elections this century have been won by less than 60 votes. Elections in FST are never dull.

The constituency was created in 1950 when the two-member Fermanagh & Tyrone constituency was split as part of the final move to single-member seats. As the name suggests, it consists of County Fermanagh and the southern part of County Tyrone. Some areas south of Omagh were removed for the 1983 election, after which it consisted of the whole of Fermanagh and Dungannon (later Dungannon & South Tyrone) councils. Boundary changes for the 1997 election removed 6 wards around the town of Coalisland, north of Dungannon. This area was strongly Republican and its removal boosted the Unionist vote. FST was unchanged in 2010, though the Boundary Commission has twice suggested linking Fermanagh with Omagh instead of Dungannon in its provisional proposals. It is a sprawling and mostly rural constituency stretching for nearly 70 miles from Lough Neagh to Belleek. Since the resettlement of the islanders of St Kilda in 1930, Belleek has been the westernmost inhabited place in the UK.

While the constituency does include areas of prosperity (parts of Enniskillen, Dungannon and the area around Moy) income levels are below the regional average. The percentage of the population living in households of social grade AB was only 12.5% at the 2011 census, the third lowest in NI. 57.7% of the population had a Catholic community background, the seventh highest in NI. This represented a 2% increase on the 2001 census and, despite the close results, the recent trend has been towards Nationalism. The Protestant population forms a majority in the area between Dungannon and the Fermanagh border, the eastern part of Dungannon and north and central Fermanagh. The first of these areas includes Clogher, the last place in NI to lose its city status, which occurred with the 1801 Act of Union. Most of southern and western Fermanagh is 75-80% Catholic, with Enniskillen reaching 65%. In the 2016 Brexit referendum, the constituency seems to have split on sectarian lines, with 58.6% voting remain.

Both the DUP and SDLP were late organising in parts of Fermanagh. In the former case, this ensured UUP hegemony. In the latter case, this left the field clear for independents and smaller Republican groupings such as Unity, the Irish Independence Party and, from the 1980s, Sinn Féin.

The first contest in 1950 was won narrowly by Cahir Healey, who had represented the predecessor constituency until 1935. Aged 72, he was one of the oldest returnee MPs. He held the seat in 1951. The 1955 election saw a narrower victory of 261 votes for the Sinn Féin (SF) candidate Philip Clarke. However, as Clarke was in prison, he was unseated by an election petition and his sole opponent, the UUP’s Robert Grosvenor, was declared elected in his place.

At the 1959 election, the Nationalist Party withdrew their support for SF, instead urging their supporters to boycott the election. This led to a swing of nearly 32% from SF to the UUP, largely down to differential turnout. As a result, Grosvenor won with 81%. At just 61%, the turnout was way below usual. In all other elections from 1950 until the mid-1980s, FST consistently produced one of the highest turnouts in the UK, never falling below 86%.

Nationalist/Republican splits in 1964 and 1966 allowed the UUP to win. However, for the 1970 election, a pact was agreed under the appropriately titled “Unity” label, with its candidate, Frank McManus elected. However, in February 1974, both Unionist and Nationalist sides were split, but the more even split on the Nationalist side – with the SDLP standing for the first time - allowed UUP leader Harry West to become the new MP. His tenure was even shorter than McManus’. Nationalists agreed a common candidate, local pub owner Frank Maguire, who won as an “Independent Republican.” This gave West the unwanted distinction of being the only MP elected in February 1974 who lost his seat later that year and never returned to the Commons.

Maguire’s attendance at Westminster was low, but he did play a significant role in that parliament. Usually voting with Labour, he refused to back them in the key vote of confidence in 1979, flying to London to “abstain in person” as he put it, resulting in an early General Election. Maguire’s actions led to disputes within the local SDLP branch over whether to stand. Though they voted in favour of withdrawing, this caused controversy, and one member, Austin Currie, who had previously represented East Tyrone in the NI Parliament, ran as Independent SDLP. However, the Unionist side was also split, with Vanguard splinter group the United Ulster Unionist Party opposing the UUP. This allowed Maguire to hold with a majority of nearly 5,000.

Maguire’s untimely death in 1981 at the age of 51 came at a turbulent time in NI politics. The Hunger Strikes in the Maze Prison had sharply polarised the region. With Unionists agreeing a common candidate, former MP Harry West, Nationalists sought to do the same. Maguire’s brother Noel announced he would stand but stood down after implied threats leaving the way clear for Bobby Sands, the leader of the IRA prisoners, to face West in a straight fight. In a by-election which attracted international attention, Sands beat West by 1,447 votes on an 87% turnout in which over 3,000 ballot papers were spoilt.

Sands died on hunger strike 26 days later. The government rushed through legislation (The Representation of the People Act 1981) to prevent another prisoner standing in the second 1981 by-election. Though some smaller parties and fringe candidates stood, Sands’ election agent, Owen Carron, standing as “Anti-H Block Proxy Political Prisoner” was able to increase the majority over the new UUP candidate, Ken Maginnis.

Sands’ and Carron’s elections had wider significance, proving to Sinn Féin that an electoral route was viable. At SF’s 1981 conference, senior strategist Danny Morrison confirmed a change stating: “Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?” This was dubbed the ”Armalite and Ballot Box” strategy and saw SF contest elections from 1982 onwards. Arguably, FST played a key part on the first step on the road to the IRA ceasefire the following decade.

The SDLP, despite internal division, had not stood in either by-election, but they stood in the 1983 general election. This split in the Nationalist vote allowed the sole Unionist, Ken Maginnis of the UUP to win comfortably, by 7,676. Continued Nationalist divisions allowed him to hold the seat with ease until his 2001 retirement.

One of the more significant events in The Troubles occurred in the constituency. In November 1987, an IRA bomb detonated at the cenotaph in Enniskillen, killing 11 civilians. The murder of so many people, many of them elderly, commemorating war dead appalled many Nationalists and led to a significant backlash against Sinn Féin. In the 1989 local elections, the party lost over a quarter of its council seats, with losses heavier in the west of NI. Fermanagh proved the worst, with the party losing 4 of its 8 seats (another would be lost in 1993.) The party’s support would not return to its 1985 until 2001, well after the IRA ceasefire. The bombing is seen by many as a key turning point in the Troubles and one of the catalysts for the peace process of the 1990s, which led to the Good Friday Agreement. These events led Sinn Féin to realise that the "bullet and ballot" strategy was unviable.

The Agreement led to significant tensions between the two main Unionist parties, so when the UUP selected James Cooper, a staunch supporter of the Agreement, to succeed Maginnis, the DUP refused to endorse him. Instead they backed independent William Dixon, who had been badly injured in the Enniskillen bomb. As was usual in NI elections before 2010, counting did not begin until the Friday morning. FST was the final UK constituency to declare at after 10pm, a full 24 hours after polls had closed. The result was a bitter one for the UUP as Sinn Féin’s Michelle Gildernew beat Cooper by 53 votes. In reality, the margin was even closer. The UUP cried foul, launching a legal challenge and pointing out that a polling station in the mostly Catholic village of Garrison had remained open after 10pm, allegedly after the presiding officer had been threatened by Republicans. An election court found that this had indeed occurred, but that the number of ballot papers issued had been no more than 20, insufficient to affect the result, which was upheld.

For the only time to date, both the UUP and DUP stood candidates in 2005. Although the DUP overtook their rival for the first time, this allowed Gildernew to hold by 4,582 votes, a relative landslide in FST terms.

With relations between the DUP and UUP improving in the late 2000s, a common independent candidate was agreed for 2010: former Fermanagh council chief executive Rodney Connor. With the SDLP refusing to stand down, it was expected that this would return the seat to Unionist hands. However, Sinn Féin portrayed Connor’s selection as a “sectarian pact.” This allowed them to significantly squeeze the SDLP vote. The first count put Connor 10 votes ahead. SF requested a recount, which gave Gildernew an 8-vote lead. A second recount cut this to a 2-vote lead. A third and final recount gave her a 4-vote victory. Subsequent events were a rerun of 2001. Unionists mounted a legal challenge, alleging ballot paper irregularities. However, an election court upheld the result, finding that only 3 ballot papers could not be accounted for, insufficient to affect the result.

Having held on in 2010 and with a general trend towards Nationalism, it was expected that Gildernew could beat the sole Unionist in 2015 as well. In a result that was somewhat of a surprise, she lost by 530 votes to former UUP leader Tom Elliott. Like many of his predecessors, Elliott’s tenure was short. Two years later, Gildernew reversed the result, beating him by 875 votes.

2019 saw a slight SDLP recovery and both the UUP and SF decline. This resulted in Gildernew’s majority falling to just 57 votes, the smallest majority of the election. Despite the trend towards Nationalism, Unionism’s greater success in agreeing pacts means the drama here will likely continue.